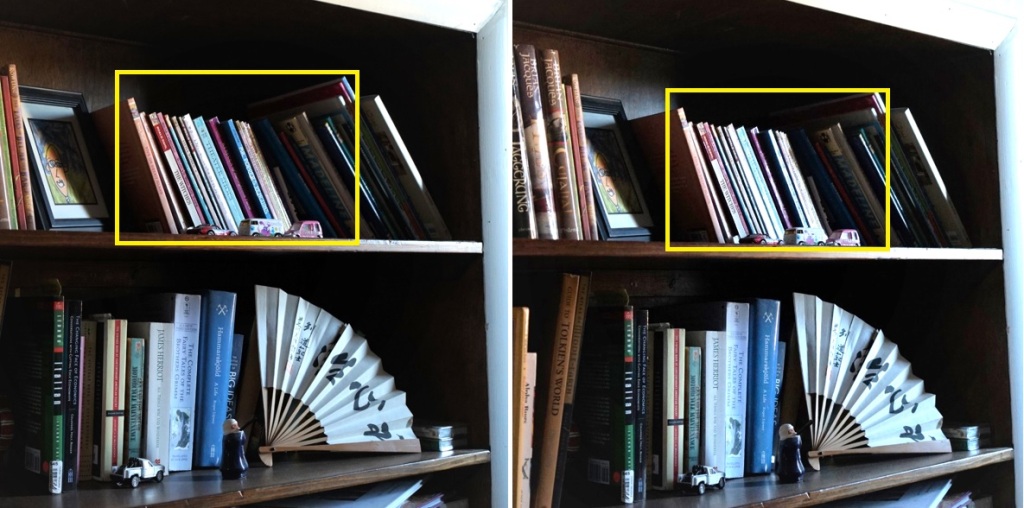

Even in the dull light of the cloudy morning, the surface of this plastic covering of the paperback book presents an eye-catching sight. From one position only the pattern is visible. But from directly overhead, looking down, only the book art and title can be seen (the clear plastic is almost invisible). In-between the first standpoint and the second one, this photo shows the semi-transparent effect of reflecting part of the light, while also allowing some of the light to pass through the plastic and shine on the book’s title and colorful background art. Something similar happens with other surfaces that can both reflect and transmit light through them: the water surface, window glass, or clear plastic packaging, for example. Any disturbance to the surface tension or texture can block vision inside and beyond the surface: rough water, hand-blown or pebbled or sandblasted glass, or grubby fingerprints on the plastic packaging, for example.

Insights to draw from this image fit into two categories. One lesson is that surface disturbance draws attention to the surface and thereby obscures what lies on the other side of the surface (below the surface). Outside of the world of optics and speaking more metaphorically, frivolous lawsuits, procedural objections intended to muddy the waters or delay the process, and the authoritarian government disinformation habit of flooding public discussion with extraneous, contradictory, or loud distractions or “what-aboutism” are examples of surface disruption.

Another lesson to draw from this image is that one’s standpoint is essential when turning transparent (e.g. looking at the book cover from directly above) to semi-transparent like the photo to fully opaque (e.g. seeing the book cover from an angle even more oblique than the lens position in this photo). Taking this observation more generally, the same is probably true of the above examples of surface distraction and “noise.” By changing one’s standpoint, some or all of the reflective confusion can be overcome so that the underlying subject is visible.

Looking at the relationship of surface to what lies under the surface, the matter can also be looked at in reverse; not with regard to reducing glare and pattern of the outer layer but going the other way: finding uses and value in amplifying the surface to achieve semi-transparency or perhaps something nearly fully reflective and thus almost opaque. One purpose in adjusting the angle of reflection of light source, surface, and lens/viewer is to draw attention to the patterns on the surface (e.g. frost tracery). Another reason could be to make visible the depth that lies between the viewer and the underlying subject (to stop taking for granted the intermediary parts). Or perhaps there is meaning that comes from obscuring some degree of the subject so that is will not be readily seen, but instead the viewer will be forced to struggle a bit to identify and understand what lies there; leaving something to one’s imagination.

No matter the scenario, it is good to recognize how the semi-transparent subject can shift from fully transparent to fully opaque, according to standpoint and/or movement of light source. In this way, when next faced with glare or its absence, a person can pause and consider moving in order to gain a new angle on the matter.