So many possible subject appear to the eye of the beholder.

Oftentimes a location offers multiple subjects to feature in a composition. Use too wide of a frame and the main subject is lost among the other elements of the picture. Use too tight of a frame to isolate the main subject and what may be integrally related to the visual point of interest gets left out, possibly giving a false representation to the viewer of the true nature of the subject or setting. When faced with more than one visual attraction, each person seizes on different points of significance in the subjects to frame, some more abstract or conceptual than others.

One photographer could see the world of potential photographs in terms of simple, bold design with just a few colors and strong lines to make the best resulting picture. Another person might not find those strong lines and colors to be significant and instead focus on personalities or events that visually communicate drama or its emotional complement, tranquility. Still others may hunt for subjects that tell a story or suggest processes and changes that are only momentarily frozen by the click of a shutter. Depending on the person’s interests, the favorite view could come from a macro lens for the world up close, or maybe it is a telephoto lens for cropping tightly around a central subject, or else perhaps it is a wide-angle lens that most often shapes the person’s eye for framing a subject with a wide context.

The process by which humans make meaning, recognize meaning, or find meaning involves connections: an item is seen in relationship to similar items, or by strange incongruity that item stands in contrast to the other one. Connections can be made with nearby things, or tied to other items more abstractly (figuratively, conceptually, symbolically). By controlling the composition frame and juxtaposing a main subject it is possible for the photographer to emphasize certain connections (or to obscure, block, or disregard other connections) above and beyond other possible relationships.

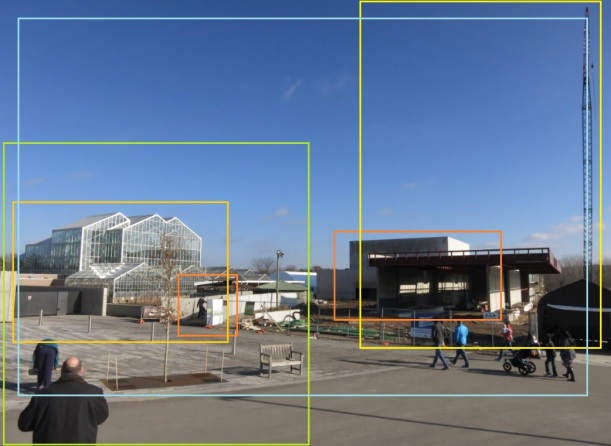

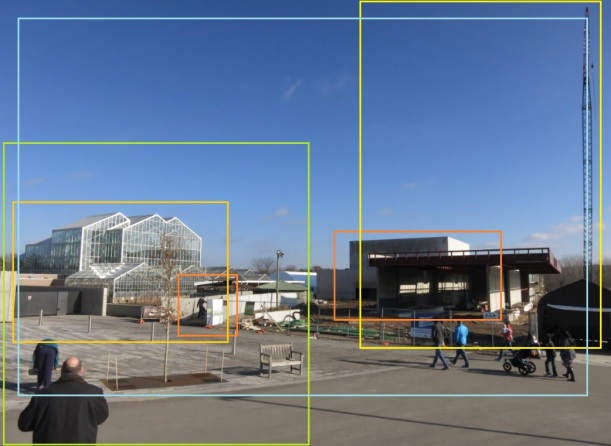

The above photo shows an ordinary scene at the edge of the parking lot for the Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids, Michigan in November. The strong light, clear air, and clearly defined shapes offer a variety of possible subjects to foreground and to frame. Rather than to compare the merits of one compositional frame against another, the point of this essay is to suggest some of the consequences that come from imposing one size frame instead of another. Put another way, how much context is needed when presenting a subject? This may not be something suited to a rule, but this ability to judge the right frame certainly does grow sharper through experience.

Undoubtedly there are merits to each of the overlain crop lines used in this illustration to trace each of the many possible ways to engage with the scene and to capture one or more compositions. Even the different aspect ratios (square versus 16:9 versus 3:2 versus 4:3) and orientation (portrait versus landscape) contribute something to the subjects within this larger scene. But above all else, what happens when the borders are drawn around a subject tightly (little context) versus more broadly (wider context), possibly to include meaningful juxtaposition of foreground, middle, and background in relationship with the main subject?

A tightly framed shot will fill the viewer’s attention with the main subject, inviting close scrutiny of the surface, texture and color, line and mass. And the nature of still photos to freeze the subject allows something moving to be studied endlessly, although the essential aspect of dynamism, diachronic process, and behavior or response is downplayed by freezing the subject to view its structure or design. There is a lot that is gained by such a clear and tangle-free portrait of the subject. At the same time much is excluded or omitted, too: the motion/longitudinal interaction of the subject with its surroundings is one absence. Another is the tendency to abstract or distill the subject, treating as a type, a symbol, a thing freed of (developmental) past or future and timelessly existing in that frozen moment. The subject taken out of context becomes objectified and impersonal; more (inert) object than (autonomous) subject.

Taking the opposite approach and framing a subject in wide context, what are the consequences for people who view the picture? In all compositions, tight or loose, there is always an edge of the frame that leads the viewer to wonder what lies just outside of view. But with a shot that gives generous context to the main subject, some of the immediately adjacent space and subjects can be seen surrounding the main subject. In other words, there is less guessing for the viewer, because the contiguous space around the subject is given in wider views.

Suppose for a moment that a dozen photographers faced the same scene (above photo, for instance), and that each one seized upon a different significance than the others. Taken individually, some pictures might appeal to one viewer, but less so to the eyes of another viewer. More interestingly, though, when all 12 resulting photos are viewed all together, a few insights emerge. (1) Each shot has integrity to itself – it is a true likeness and faithful representation of a moment and framing of a particular subject. (2) The universe of other compositions is missed or overlooked as a consequence of capturing that photographer’s own specific engagement with the subject; sort of an “opportunity cost” (the price of committing to one picture is the many other shots that could have been taken instead). (3) Synthesizing the diverse compositions, it becomes clear that no single framing or articulation of the scene is the whole truth or complete essence of the subject. (4) No matter how tightly or loosely framed the composition, there will forever be something that lies outside the frame; out of view. In other words, (5) a larger context of meaning can infinitely be expanded around any given composition.

Summing up, when you come upon a scene or subject to photograph, consider the context just beyond the boundaries of your selected framing of the composition. Then ask if the significance more or less fits into the frame, or importantly exceeds the boundaries of that frame. By recognizing how very different the resulting photos of a given place can be, according to the eye and experiences of the photographer, this simple question opens up your perspective so that the eventual shutter release will enjoy a momentary delay for reflection, and possibly also result in a second variation on the composition that lets just a little more context and meaning into the picture.