“I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.” – Garry Winogrand

In the days before digital pictures, each shot on the film roll consumed one frame of 12 or 24 or 36 exposures. So the psychological result of this scarcity and expense and finitude was to think twice before committing to the shutter release. By contrast today one’s picture taking is limited only by battery life (but a spare will extend the shooting) and memory card limits (cheaper and more capacious by the year). So as a practical matter those three confinements (scarcity, cost, fixed number of shots) vanish in digital photography.

A person today can shoot a burst of shots without thinking, whereas a film photographer has to change rolls every few dozen exposures (and a sheet film photographer has to make each shot be a prize-winner). So one difference in working method that culminates in shutter release is that digital enthusiasts can respond to the slightest eye-catching subject without worry about depleting the stock of available recording medium. But with film there is a kind of subjunctive mindset: “how would it be,” “what could it look like,” or “should I capture this subject.” Those expressions are classified as conditional or potential statements, but English also has an archaic, poorly used and seldom discussed vestige of the subjunctive form of expressing an idea. LOTE (languages other than English) often have a richer, more commonly used subjunctive by contrast. Here among photographers the approach is to suppose it were true; imagine it were accomplished; accept (temporarily) the proposed situation has taken place already. In other words, a film photographer then and still now approaches possible subjects of composition with the thought, “if it were photographed, then how would it look?,” much in the spirit of the opening quote from prolific roll-film photographer, Garry Winogrand, who died with hundreds of photographed film rolls as yet undeveloped and printed for review.

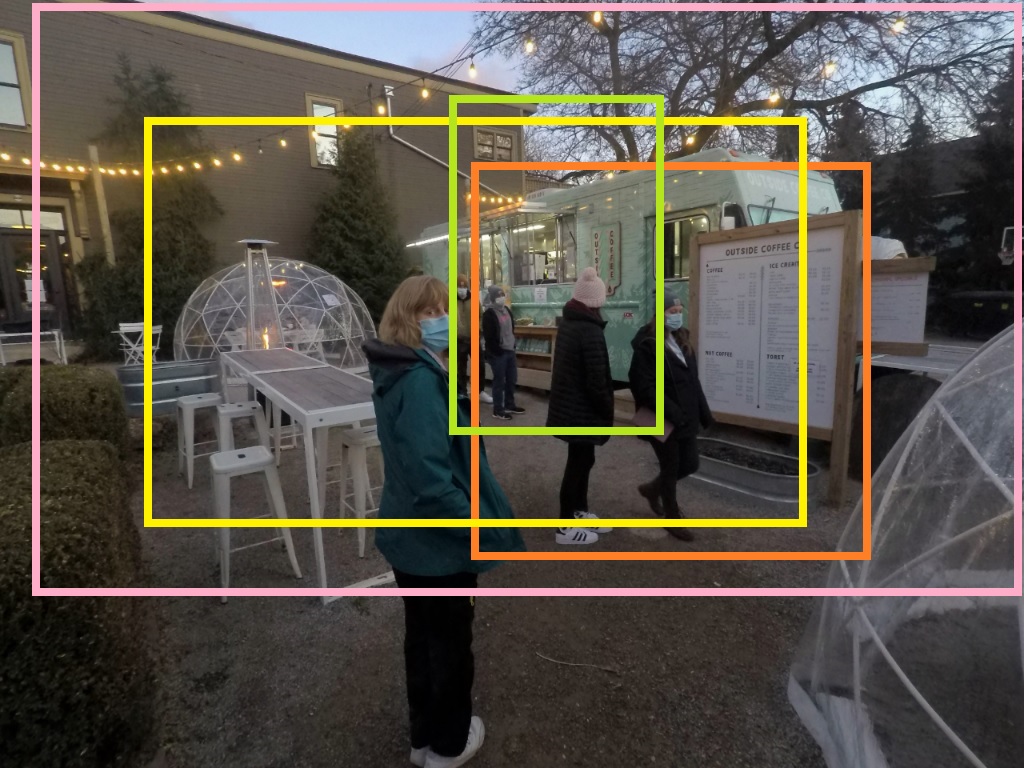

So a film photographer might approach this dusk location with coffee and other hot-drink customers placing their orders by glancing at the overall scene, then asking herself or himself “if I were to shoot the picture this way, then how would that turn out” (since the sparkle that catches one’s eye does not always translate well onto film or camera sensor), or “would this be a good photo, I wonder”? Given the limited number of exposures on the roll of film loaded on each camera carried, a consideration –verbally articulated, or as a gut-reaction– normally occurs before committing to taking a picture. By contrast, Digital photographers seldom ask themselves that question, instead leaping from initial visual attraction directly to executing the exposure. That is not to say that digital photographers are condemned to shooting first and asking questions later; nor that a slower pace and deliberateness is exclusively limited to the working conditions of film. After all, a digital photographer with big, clunky gear; or a person dedicated to using a tripod to frame a composition before releasing the shutter is bound to proceed relatively slowly. And among film photographers there have been rapid shooters able to respond to fluid situations. But overall the nature of film versus digital photographer does tend to make the slower photographers more mindful, reflective, and deliberate in composition decisions. For a digital photographer, and especially for a point-and-shoot or cellphone photographer, it is not impossible or improbably to frame carefully, focus deliberately, and edit scrupulously. But to embody the film photographer’s mindset and work within the convenience of digital photography does require added care and much practice to establish the habit of seeing this way.

Thus to all digital photographers out there, let this be a challenge to take up: before falling into familiar point-and-shoot routines, instead ask the subjunctive question “if that it were” then how would the finished photograph look? By considering the subject, whether it is static or in motion, before raising the camera and capturing the scene, the relationship between subject and photographer shifts slightly. Gone is the “grab and run” of digital snapshots, and in its place is quiet study and reflection that may or may not lead to a shutter release. Perhaps this idea of pretending the number of shots is limited and must be budgeted with care is too awkward or troublesome at first, but indeed there are hidden rewards to what one sees and how one sees that come from the slower pace of picture-taking.

For a glimpse of the dusk Outdoor Coffee scene in video form, see https://youtu.be/ZUJe-LsUh_I .