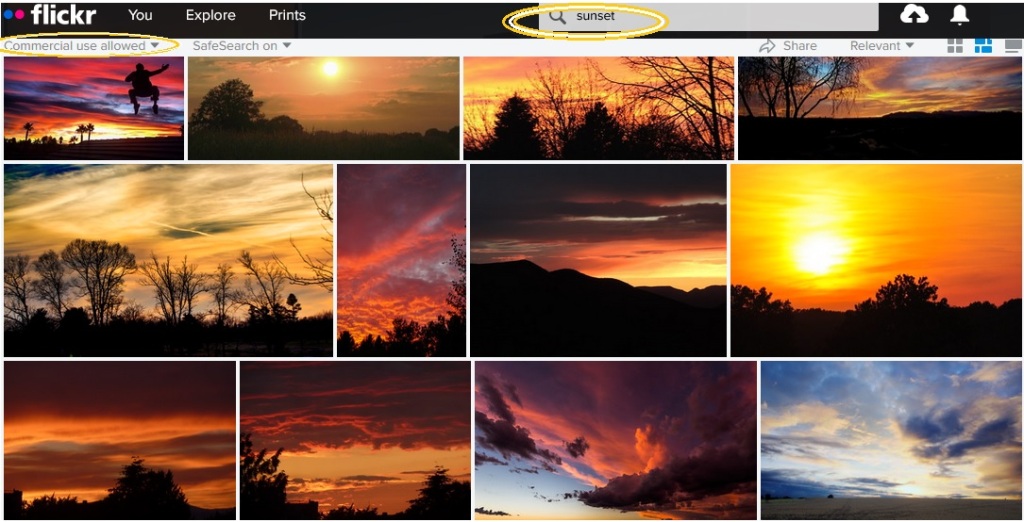

Seeing all this color concentrated in a single screen filled with images is rich food for the eyes. Just one shot would be a feast for the eyes, even for a glutton. But when all of them appear side by side, it feels oppressive; too much information. Looking at them one at a time, there is a dramatic intensity of colors present. In the realm of optics and editing, both hue and saturation seem to be increased beyond the visual experience of a person’s eye.

In real life with the unaided eye, there are times during the Golden Hour and then Blue Hour when colors are richer than usual, but those instances like the ones in some of the photos, above, are rare and last briefly. When presented as static images one after another, like the collage above, it is just too much to believe or to enjoy. One reason for this reaction to richer than normal colorfulness could be the corresponding contextual conditions surrounding such a state of affairs. That is to say, the kind of moment capable of producing such dense coloring feels uncomfortably strange: barometric and other weather conditions foretelling dangerous developments, for instance. By contrast, less spectacular and commonplace sunsets do not portend anything ominous. The normal sunsets are attractive, but such an ordinary photo does not “gild the lily,” as the poetic image goes from generations ago.

Another atmospheric condition that makes colors unnaturally saturated is particulates suspended at high altitude after weeks of upwind forest fires or even more distant volcanic eruptions. Many of the photos in the above collection of shots seem to display that degree of amplified intensity. And yet with no precursor ash in the air, it must be a function of the photo editing software that this amount of richness is ladled on so abundantly. This emotional response to “too beautiful” or “too richly colored” is a reminder that human senses, engagement, and attachment has a range of “too much” and too little and “just right.” Sometimes that sweet spot is called the Goldilocks Principle, after the children’s story of The Three Bears and the little girl who intrudes while the bear family has momentarily left their abode.

So it is not just teachings of children’s stories, The Golden Mean, and photographs that are too something: bright, dark, richly colored, altered by software or darkroom tools. The many other departments of human lives and their daily habits also have upper and lower thresholds for maintaining conditions that are normal, desirable, healthful, and so on. By scrutinizing the sunset collection, above, the same logic can be applied from photos to life overall: about recognizing and guarding those boundaries of taste, propriety, structures of meaning and making of knowledge. What is less certain, though, is precisely where the boundary of too much or too little lies. Along a finely graded spectrum, one person could put the boundary here, but another person could extend the normal range a bit more. Even the same person might move the boundary, depending on time or day, season, or who they are interacting with at the time of drawing the boundary.