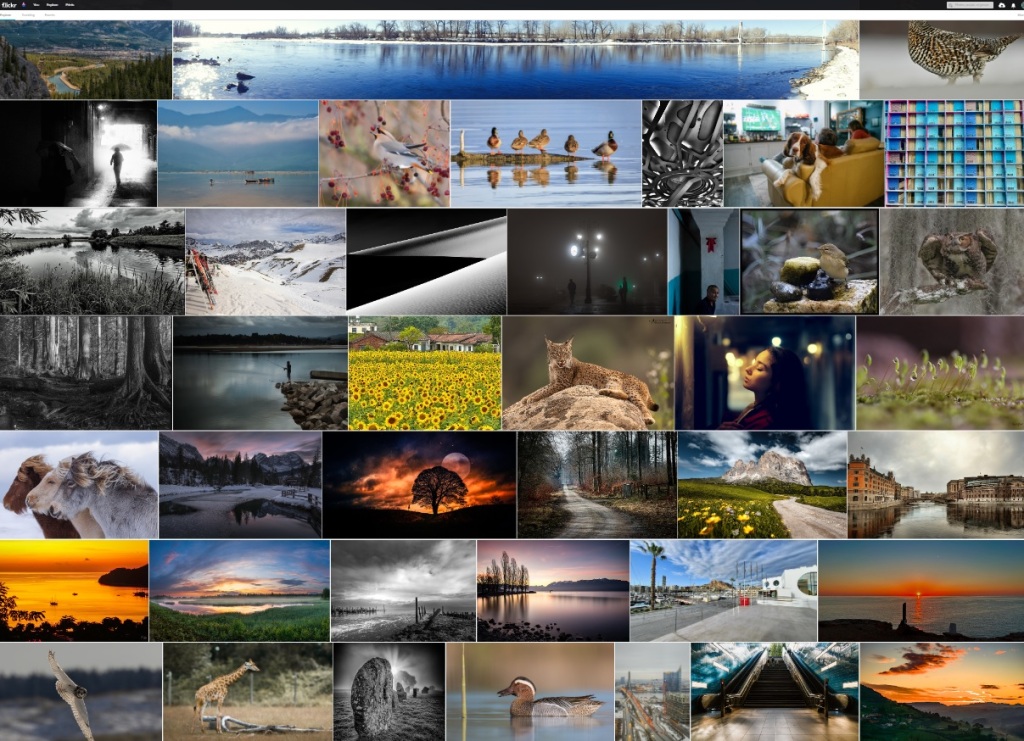

Seeing so many pictures gathered from all levels of photographic skill, location, and subject matter is astonishing in the daily set of picks online at Flickr “Explore.” This screenshot is only the top of a long series of screens to scroll and gives a sampling of what attracts the eyes of people carrying cameras who point and shoot impromptu when a scene presents itself, as well as those purposefully searching for (or creating) a composition. No matter the motivation and circumstances around the making of a given photo that the person chooses to upload for public viewing, what is universally true is that none of the seeing, recording, and communicating would be possible without first having a device to focus and capture light; i.e. camera lens and recording medium.

In order to appreciate the consequences of ubiquitous cameras (and online sharing platforms), perhaps the best way to visualize the effect is to suppose there are no cameras. While early forms of photography began in the middle 1800s (sitting for a tintype recording), it was only with the Kodak Brownie box camera that non-experts could begin to record significant things in their world of people, places, and events. Even in the 1890s, though, the number of households with a Brownie was miniscule. Large numbers of people only began taking pictures in the post-WWII generations as the Baby Boom presented an obvious subject to record at home – the growing up and family events of all those newborns. Cameras got better, cheaper, and more commonly carried. Enthusiasts multiplied. Professionals specialized in many kinds of subject and publication outlets. And then with cellphone cameras reaching similar quality to the cheap film cameras (and then exceeding them), since around 2005 or 2010 the proliferation of cellphones has made pictures of anything and everything possible; at first a novelty, then an expectation to see people snapping stills and video of things momentous or banal. And while having ready access to a camera – most often as part of a cellphone – does not mean the person considers herself or himself an adept visual observer and artist, by force of habit, people are ever more accustomed to taking photos in their own way and seeing their surroundings as “photo opportunities” – not as an afterthought, but in some cases as the main point; what makes the experience real, enjoyable, meaningful, and possible to show others, too.

What happens when more and more people are taking pictures for personal records or to document a subject or to give to others? Without having cameras that enabled cheap, easy, and convenient recording and circulating far and near, the only visual medium to represent 3-dimensional subjects in 2-dimensional form was visual art with brush, pen or pencil, for example. It could be a quick sketch or a detailed representation to scale. But most people lack such hand-eye coordination –the training and experience to see, and to record the lines and textures and colors and play of shadow and light. Instead, the average person would resort to word-images, “painting pictures with words” if they were verbally gifted. Others might buy a tourist postcard or print produced by the eye and hand of an artist to share with friends and family, or to cherish as personal reminder of a time and place.

Now with so many picture-takers, the likeness of a subject can be recorded with a tap or press of a button. Not everyone cares or finds rewarding the careful composition and reflecting on the art of making a picture. Instead it is enough to capture some vestige of a fleeting moment and then rely on storytelling skills to complete the meaning. And yet as more and more people do take pictures routinely and some of them begin to refine their efforts to get better results, such as the gems that Flickr editors showcase each day at flickr.com/explore, then one’s thinking that is paired with one’s seeing and one’s noticing the details of a place and moment also changes. In other words, the habit of going through one’s day and life with a camera in hand or at the back of one’s mind means that things like foreground, juxtaposition, shadow detail (penumbral light), mixed lighting temperatures, and so on begin to stand out more and more. Pre-camera, maybe the things in the thumbnail images, above, might merit a remark or pause to admire before pressing on in one’s day. But now when one’s attention is drawn, it seems natural to frame a composition by choosing a standpoint, and angle of view, and a chosen moment to release the shutter.

A world without cameras is still visually rich, but the integral relationship between seeing and thinking is less readily sharpened without the aid of a camera to produce detailed images for scrutiny, sharing, and reflection that leads to a virtuous cycle for improving one’s seeing and recording. In short, filling the world with cameras makes it easier to pay attention to the visual (and social) environment. One’s sensibilities for light, composition, timing, and so on are amplified so that even on days with no camera at hand, one’s visual experience of a place and time is much richer, filled as it is with possible images to compose. As one’s seeing is heightened, so, too, is one’s thinking developed.